|

FEB.

28, 2019 |

|

|

A “gateway" leading nowhere in particular was dedicated at Oberlin College in 1937. It celebrates the graduation a century earlier of the first Oberlin women. In the college's earliest years, male and female students lived in its one and only building, so special care had to be taken to maintain propriety. By 1836 a larger building, Tappan Hall, had opened, and the “laws of the institution” were more strictly enforced. That year, wrote Robert Samuel Fletcher in his history, “a student was dismissed because he had ‘broken one of the fundamental laws of the institution, which is that no male student shall go into the chamber of the young ladies on any occasion without a special permission from the principal of that department.’” But let us take a closer look at the following year. On May 22, 1837, a romantic triangle departed the campus: a female student and her two admirers. One of the suitors would reluctantly climb out of the wagon after only a short distance. The other man would accompany her back to her parents' home — more than 400 miles away! |

Scandalously, this second man was a faculty member, the reverend Principal of the Preparatory Department. He had been sending love letters to the student. This may have been sexual harrasment, but it was the 19th century, so the faculty member's colleagues didn't fire him. Instead, they voted to banish her.

That's just some of the titillating gossip about the Connexion Of Male And Female Departments in the earliest years of the College. It's our latest installment of Delazon Smith's “scurrilous pamphlet.”

|

FEB.

26, 2019 |

|

|

Edie McClurg (right) was my grad-school classmate at Syracuse in 1970. Mark Evanier recently revealed that in 1997, he didn't feel Edie was exactly the voice actor he was looking for to play the role of ... |

|

|

|

|

... shrewish animated cartoon character Pandora Ricketts (left). Joanne Worley didn't quite fit the part either, nor did Rue McClanahan — though all those actresses were right there in the room, signing the guest book. But we should let Mark tell the ghostly story. |

FEB.

24, 2009 ![]() THAT

SOUNDS RIGHT TO ME

THAT

SOUNDS RIGHT TO ME

It appears that the word “that,” when used as a conjunction, is sometimes optional. A writer may decide that it belongs in a sentence. Another writer may decide it doesn't belong.

One of my college friends used “that” every chance that she got. I thought that her style must be a more elegant one, so for a time I emulated the way that she wrote. More recently, one of my colleagues kept misidentifying a 1996 Tom Hanks movie with a four-syllable title as That Thing That You Do! But I've heard journalists, striving for brevity, insist that “that” should never be used in such a manner.

However, sometimes it's necessary, lest the writer inadvertently lead the reader down a blind path.

A hockey story in yesterday's newspaper asserted, “The Penguins must get the best blue-collar workers such as Max Talbot, Mark Eaton and Pascal Dupuis have to give.” I had expected the sentence to turn out something like this: “The Penguins must get the best blue-collar workers — such as Max Talbot, Mark Eaton and Pascal Dupuis — either by trading for more such players or by acquiring them on the free-agent market.” But noooo. The sentence stopped making sense after Dupuis, and I had to go back to the beginning and mentally insert the missing “that” while reading it a second time: “The Penguins must get the best that blue-collar workers such as Max Talbot, Mark Eaton and Pascal Dupuis have to give.”

We mustn't sacrifice clarity for brevity.

FEB.

22, 2009 ![]() LOWERING

THE TRICOLOR

LOWERING

THE TRICOLOR

Jokes in a late-night comedian’s monologue typically refer, in their punch lines, to something the audience already knows. Because we’ve heard this fact lampooned before, we laugh on cue.

For example, from Jay Leno in 1990: “You can't blame R.J. Reynolds for marketing their new cigarettes at minorities and young women. They're the only ones left. All the other groups they've targeted have died!” This apparently macabre joke works only because we’ve already accepted that cigarette smoking is deadly.

I’d like to suggest that it may be time to retire one of these much-used facts. As we’re constantly reminded, at the beginning of World War II Hitler’s tanks stormed into France, and rather than risk the destruction of Paris by the overpowering force of the Germans, the French government surrendered. To that point all the other nations that Hitler had invaded had also given up. Nevertheless, ever since, jokes have been based on the stereotype that the French are cowardly.

In this month’s Funny Times, Dave Barry reviews the past year. He relates that in May 2008, Iran’s nuclear aspirations lead six nations to “convene an emergency meeting, during which they manage, in heated negotiations, to talk France out of surrendering.”

Then in July, “Barack Obama ... flies to Germany without using an airplane and gives a major speech speaking English and German simultaneously to 200,000 mesmerized Germans, who immediately elect him chancellor, prompting France to surrender.”

In the same issue, Will Durst asserts that Sen. John McCain ran the worst campaign ever. “That includes New Coke, France in ’39, and Cloris Leachman on Dancing With The Stars.”

And then this week, Carbolic Smoke Ball ran this fake headline: “British, French Submarines Collide in Atlantic — French Sub Immediately Surrenders.”

After nearly 70 years, shouldn’t we surrender this stereotype?

FEB.

19, 2019 ![]() GRAPEFRUIT

LEAGUE BEGINS FRIDAY

GRAPEFRUIT

LEAGUE BEGINS FRIDAY

Drabble

by Kevin Fagan (2018)

FEB.

17, 2019 ![]() YOUNG

WOLVES AT MID-CENTURY

YOUNG

WOLVES AT MID-CENTURY

|

Why is this young man smiling? He's “wolfing.” Having noticed a cute blonde on campus yesterday, he has now joined her on the parlor couch. She, however, is not smiling. In fact, she's leaning away from the wolf, the better to watch Uncle Miltie on TV — because it's 1950. |

|

All the 20th-century rules of propriety are being observed. Of the couple's four feet, the prescribed minimum of three are on the floor, and the parlor door has been propped open with a wastebasket to discourage surreptitious shenanigans.

But how did the young man learn the blonde's name and address? He used his Wolfbook. The cartoon above appeared on the cover. The photos inside included one particular freshman who today is an 86-year-old emeritus professor, still living near the campus.

My latest article gives you a peek at Wolfing in 1950.

|

FEB.

14, 2019 |

|

|

It was on this date 160 years ago — February 14, 1859 — that Oregon joined the Union. The new state's first two Senators were Democrats Joseph Lane (far left) and Delazon Smith. Oregon had been admitted as a free state, but Smith, despite having studied at abolitionist Oberlin College, “did not subscribe to anti-slavery sentiment.” Having drawn the shorter straw, he received the shorter term, which would expire when the 36th Congress was sworn in on March 4, 1859. Unfortunately, Oregon's legislature declined to re-elect him, so he was out. He had served only 18 days as a United States Senator. The seat would remain empty until a Republican was named in the fall of 1860. |

Decades earlier, when Delazon Smith was an Oberlin student, he also served less than a full term. “His disagreement with school policy and philosophy ... earned him an invitation to leave and not return.” Thereupon he promptly published a book telling what was wrong with the college — including even the vittles.

|

The institutional food served in college cafeterias and dining halls has always drawn complaints. That's why so many present-day students will instead send out for pizza. In Smith's 1837 pamphlet Oberlin Unmasked, the disaffected former student described far worse fare at his boarding hall. Article 5 of the Oberlin Covenant had proclaimed, “That we may have time and health for the Lord's service, we will eat only plain and wholesome food ... and deny ourselves all strong and unnecessary drinks ... and everything expensive that is simply calculated to gratify the palate.” |

|

The college's leaders therefore prohibited such sinful substances as pork and pepper and coffee and tea. Students sometimes had to subsist on bread and water, like prisoners! They were, however, allowed salt.

Smith bemoaned the ban on all types of tea, including Bohea and Imperial and Gunpowder. He claimed that folks from other towns could tell that a young man was from Oberlin by his emaciated appearance, his “lean, lantern-jawed visage.”

He was so appalled that he exclaimed, “We are led to cry out in the language of the poet!” The nine-stanza tirade that resulted is the highlight of this fortnight's installment from Smith's book, entitled Board and Mode of Living.

FEB.

11, 2019 ![]() A

GRAY DAY IN HISTORY

A

GRAY DAY IN HISTORY

On this date 172 years ago, Thomas Edison was born in Milan, Ohio. There was a college in the next county, but he never enrolled there.

|

|

On Edison's 29th birthday, Elisha Gray — who had in fact attended that college — drew a sketch in his notebook. It depicted “an electrical apparatus for talking through a telegraph wire.” In other words, he'd invented the telephone. |

The sketch was dated February 11, 1876. Alexander Graham Bell's patent drawings wouldn't be filed until three days later!

My latest article tells about Elisha Gray, The Edison of Oberlin College.

FEB.

8, 2019 ![]() THESE

BILLS ARE CONFOUNDERATE!

THESE

BILLS ARE CONFOUNDERATE!

|

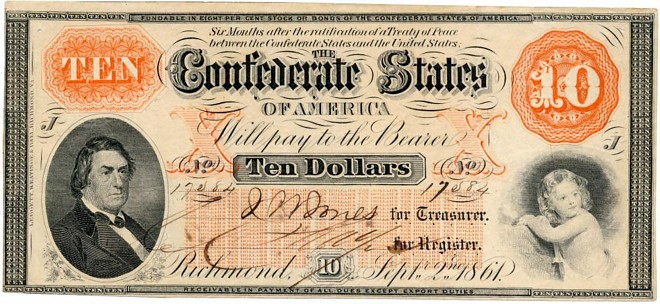

Here are three 10-dollar bills that won't buy you a hot dog. The first is play money, of course. The second is smeared because it was printed poorly in some guy's basement; it's counterfeit. And the third is Confederate. In the early 1950s, when I was beginning to read, I didn't know much about history, but I did run across stories about hapless folks being paid with worthless money. Sometimes it was called “counterfeit” and sometimes it was called “confederate,” and I thought those similar words must mean the same. Back then, a few Civil War veterans were still alive. Confederate currency was less than a hundred years old, and it was still mentioned occasionally. |

|

Now it's more than 150 years old, and you don't hear about it anymore — unless you're a collector, which I'm not. However, the many variations of these “graybacks” and other denominations are interesting.

Below is a note from the third series, issued in 1861 and signed and numbered by hand. Although backed only by bonds, within the Confederacy it was supposed to be “receivable in payment of all dues except export duties” and it would have been worth real money if the South had won the war. “Six months after the ratification of a Treaty of Peace between the Confederate States and the United States, the Confederate States of America will pay to the bearer Ten Dollars.”

The man on the lower left is the CSA Secretary of State, Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter. To balance the design, a stock image of innocence was chosen for the lower right. Later it was discovered to be a vignette of one Alfred L. Elwyn. But in 1861, Elwyn was no longer a child. He had graduated from Harvard and co-founded the Pennsylvania Institution for the Blind as well as a school for mentally disabled children. Now he was serving as the treasurer of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. And, of course, he was an abolitionist.

|

|

One of the pleasures that youngsters receive from playing with scale models, like dollhouses or model train layouts, is a sense of empowerment. As they tower over the Lilliputian scene below them, they are no longer children; they have become giants, and they're in control of all they survey. I was 14 years old, and the Ohio State Buckeyes were NCAA basketball champions, when I realized it might be fun to watch a televised basketball game not as a picture on a screen but as a three-dimensional miniature. |

Imagine a basketball arena reduced to 1/20 scale, with a court the size of a Foosball table and the players four inches high. You and your friends gather around the table and watch the action from any angle you choose. Or maybe instead of little athletes, you could see little actors performing a play. I actually wrote up my idea as an essay, now long lost, for my eighth-grade English class.

How would it work? I guessed that the positions of the players on the court could be detected with some sort of radar beam, or perhaps with one of those newly-invented "lasers." That would constitute the camera.

In your living room would be the receiver, a transparent rectangular cube about four feet on a side. Inside the cube, electronic circuits would precisely schedule the firing of millions of little guns, shooting tiny particles from one side of the interior to the other. The guns would be timed so that 30 times a second, the particles would have reached positions in space corresponding to the surfaces of the real players. At that instant, a strobe light would fire, illuminating the particles and forming ghostly images of miniature players. A thirtieth of a second later, the next firing of the strobe would reveal a new set of particles in slightly different positions, and your eye would fill in the gaps. Of course the expended particles would fall to the bottom of the box, and eventually you'd have to empty the litter tray like a birdcage.

My English teacher Mrs. Endsley said that she had no idea what I was trying to describe, but it certainly sounded clever.

Half a century later, in the January issue of Broadcast Engineering, Anthony R. Gargano muses about the state of television technology. He seems to share my vision from long ago.

Further into the future is holographic television, a technology that's in the Stone Age today. During its recent presidential election reporting, CNN used a scheme requiring 35 high-definition cameras to capture not a true hologram but a 360-degree image of a single reporter to transport her to the studio set. Was it holographic video? No, but it's certainly food for thought. Clearly, we are in the early stages, taking small steps on the road to delivering the virtual reality of 360-degree holographic video to the home.

The MIT Media Lab has demonstrated the rendering of full color holograms as 1-inch cubic images that are updatable at video rates of 20 frames per second. A research group at the University of Arizona demonstrated updatable monochromatic holograms at the size of a 4-inch cube.

Key challenges in progressing true holographic television are the sheer amount of high-speed memory and the computational horsepower required to generate motion video. Given that many of today's cell phones have more computer power than the first space shuttle, clearly it's not a matter of if but just a matter of when you can watch that Sunday NFL game with 3-D players running on top of your coffee table-like imager as you walk around it checking the action and the views from end zone to end zone.

The proposed technology may be completely different, but my dream from 1960 is still alive!

FEB.

3, 2019 ![]() STAGING

STAGING

It was the second Tuesday of September in 1969. Some 120 miles to the southeast, they were still cleaning up from the Woodstock music festival, though it had been over for three weeks. I myself, however, was on the campus of Syracuse University. With about 70 other young adults, I was joining Sequence 22 of a Master's degree program in Radio and Television.

|

We entered the gleaming marble lobby of the Newhouse Communications Center. (Two more units have since been added, and this building is now known as Newhouse One.) |

|

|

|

Publishing billionaire S.I. Newhouse's antique printing press stood next to the lobby's impressive double staircase, reminding us of the roots of our chosen field: communication. He had given the money to construct the Center, which had been dedicated by the President of the United States just five years before. |

|

|

|

But over the next few weeks, I became interested in the staircase itself. Not the tangled Pegasus on the wall. Not even the Newhouse quote below it:

A

free press must be fortified No, I was fascinated by the bottom four steps. "You know,” I thought, “this almost constitutes a ‘thrust’ stage, a good place to present Shakespeare. |

|

|

|

“All we'd need to do is punch a few holes for entrance doors. We could even add an upper window at which a singer or a Chorus or a deus ex machina could appear without the need for a machina.” I sketched my concept of the lobby redesigned as a theater. Now, almost 50 years later, I've added arrows to indicate those doors. The staircase and the drawing are in this month's 100 Moons article. |

FEBRUARY

2019

FEBRUARY

2019