Behind

Grey Gables, part one

(Part

two is here)

Written

April 30, 2013

In a world where college students are locked in their dorms every night to protect their innocence ... in a world where coeds are allowed visitors of the opposite sex for only two hours a week, and then only if the door remains ajar and three feet remain on the floor ... in a world without computers and without cell phones, where music lovers resort to Morse code to flash their requests ... a group of young scientists with names like Edison and Fermi take over an abandoned garage behind an old gabled house.

|

There they conduct experiments that will change their world, experiments that will help bring men and women together. These experiments are called RADIO. |

|

|

|

Almost 40 years after a group of enthusiasts organized a college radio station at Oberlin — and almost 20 years after my own graduation from that college — we alumni held a reunion in 1988 and recorded our memories for a WOBC Oral History. The following article is based on portions of the first 15 years of that history. I’ve rearranged the comments. If you happen to have a copy, page numbers are given for reference {like so}. Some of my information comes from other sources. |

On first reference, the names of some speakers are highlighted in red; they’re quoted again later by first name only, and you many want to scroll back up to the red letters to remind yourself who “Roger” is. I sometimes wish lengthy newspaper articles would do the same.

The Great Fire of Louisville

Roger

Brucker ’51

had always been a radio nut. As a youngster in the 1940s, he

would listen to his radio under the covers in the dark of night until

his mother would tiptoe in and catch him. {4}

Roger

Brucker ’51

had always been a radio nut. As a youngster in the 1940s, he

would listen to his radio under the covers in the dark of night until

his mother would tiptoe in and catch him. {4}

“As a child,” Fred Anderson writes, Roger “was fascinated with the unknown, always curious to discover what amazing things existed beyond his backyard boundaries.” He would go on to spend more than 50 years exploring Mammoth Cave in Kentucky and writing several books about spelunking.

When he enrolled at Oberlin College in Ohio in 1948, his freshman roommate was Bob Chamberlain ’51. Their dormitory was known as the Men’s Building, and they were assigned to take their meals at Talcott, a women’s dormitory a block away.

The roommates learned that others at their dorm, including Jim Pierce ’52, had set up a wireless oscillator. Because this pirate radio transmitter could broadcast from the Oberlin Men’s Building, they called it WOMB.

Roger remembered that listening to programming from “inside WOMB” was very risqué at the time. “There was a good bit of conversation about it around the dinner table and afterwards.” Roger and Bob used their own wireless oscillator “for parlor magic at Talcott — it enthralled the girls.”

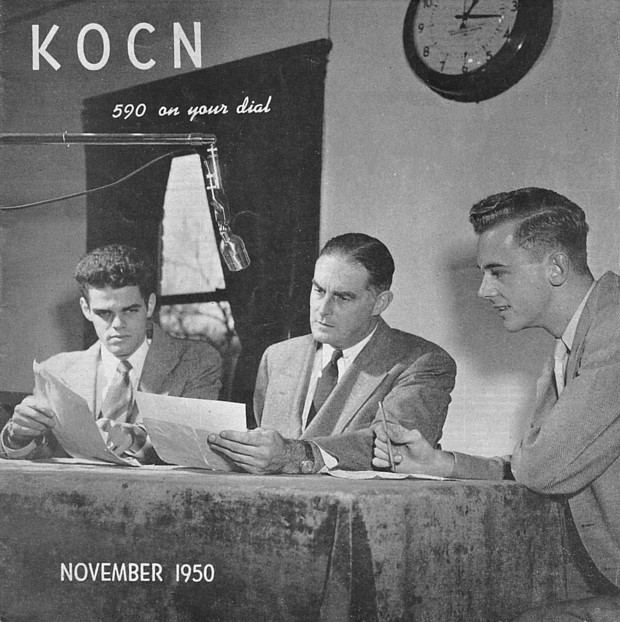

When a real radio station was formed later, they chose KOCN as their the call letters: OCN for Oberlin College Network, and K to make it distinctive. {8} But the K was “an improper prefix” for a station east of the Mississippi, noted Don Burr ’55. “We changed the call sign from KOCN to WOBC in 1952 or 1953 because we were getting pressure from the outside. We had a fair amount of difficulty getting WOBC cleared by the FCC. Even then there was some conflict with other stations.” {13}

Back at Men’s Building, Marty Doudna ’52 was considered a trusting soul. He was from Louisville, Kentucky, and a future student of his, John Burnett, would remember his deep voice, his “sprightly walk, a perpetual twinkle in his eye and smile on his face.”

The radio nuts brought Marty into someone’s room and told him that they believed they’d been able to tune in a Louisville radio station. The weak signal, of course, was actually coming from an oscillator upstairs.

Suddenly the program was interrupted to announce that a fire was consuming all of downtown Louisville. Marty was horrified. “My God, I hope it doesn’t cross Center Street,” he exclaimed. Somebody slipped out of the room and went upstairs to say that the fire’s got to cross Center Street. Soon the pirate station was delivering the latest bulletin: “Battalion Three Chief reports that the fire has leaped across Center Street and is now...”

Roger recalled that a decade before, Orson Welles had done it first and much better with his “War of the Worlds” fake newscast. But practical jokes like this were a lot of fun. “These are the kinds of experiences that kindled in a few people the idea that there ought to be a radio station.”

He continued, “There was a widespread popular view that radio was a good idea, was necessary and needed. There was no appreciation by most people of the practical difficulties of bringing it about. Certainly there was no understanding by the people who listened to it of the long hours and the kind of monomaniacal dedication and obsession necessary to bring 50 or 100 hours of programming.” {13}

Politics and Frequencies

In the winter of 1949, Roger was an editor at the HI-O-HI, the college yearbook. His mentor, D.A. Henderson ’50, “taught me a lot about how you accomplish things at Oberlin. You have to get your hands on the money, and that money comes out of the activity fee, and so it was very important to be able to have a lot of influence with the student council.”

That summer, Roger got a job in the electrical department of Buildings & Grounds. Coincidentally, B&G was moving out of its office building at 32 East College Street, across from the Apollo Theater. That was another key connection. At B&G Roger worked with Jim Reynolds ’50, an associate editor at the student newspaper, the Oberlin Review. Jim was also interested in starting a radio station. {5}

If an unlicensed campus-wide radio station were to become a reality, it still would have to abide by FCC regulations. The station couldn’t broadcast by spewing its signal, called “radio frequency” or RF, from a big antenna. Instead, individual wires would contain the signal and carry it from the studio transmitter to various individual dormitories. Buildings & Grounds would need to be involved.

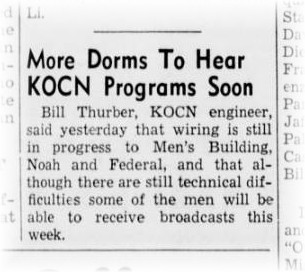

Bob said, “We chose an AM frequency of 590 kilocycles — now called kiloHertz — because that was the quietest spot on the band. We devised six potential methods of transmission, all of which failed. So Ed Stark ’53, an assistant technician, came up with the idea of using what was called the police call line. It was basically a twisted pair with lead sheathing. Stark noted that we had this wonderful twisted pair going the entire length and width of town, so why not put a signal on it and somehow connect the police call line to the 110-volt secondary circuits of each of the dormitories? A connection unit had to be designed that was safe, that would pass the radio signal but also isolate the house circuits from the call line. We eventually took it to Underwriters Laboratories, which certified its safety. So we went into mass production and built about 200 of these little boxes.” {7-8}

Bill Waite ’60 studied electrical engineering later and learned that “in order to couple a signal into a system, you really need to know something about the impedance that you’re coupling into. Because nobody knew the dorms’ impedance, these boxes couldn’t match it. In fact they didn’t. They just acted as bad terminations on the transmission lines. Consequently there were all kinds of reflections from them — radiation — and that was what was going into the dorm.” {16}

Frank Porath ’58 realized that “the boxes were not an electrical connection, they were a political connection. Putting them through Underwriters Laboratories was a tremendous achievement, but Underwriters doesn’t care whether it actually works. They only want to know if it’s safe, and that was the key. So what if it was spraying RF? That was the whole point; get a little bit of RF near the dormitory and maybe they could receive it.” {17}

“By the time I came to Oberlin,” I recalled, “the AM carrier current system included a lot of hum. You were getting as much 60 cycle as you were 590 kilocycle. Gary Freeman ’70, one of the engineers, believed the quality would be a lot better if we put mini-transmitters in the dorms. I believe 100 milliwatts was the maximum power. He wired up a number of dorms with these little things, but I don’t know how he did it.” {41}

My speculation is that Gary modulated the station’s audio onto a second, lower Intermediate Frequency (IF) that he sent over the same transmission lines as the RF. At each dormitory he replaced the old UL-approved box with a box of his own design that properly terminated that branch of the transmission line to eliminate the random leakage, upconverted the IF to 590 kHz, amplified it to a tenth of a watt, and broadcast it over a stub antenna. These microtransmitters, small enough to stay within FCC power regulations, sent their signals only a hundred feet or so, but that was enough to cover the dorm.

In fact, several of us felt that their signal sounded better than our main signal, which by then was emanating from an aging 10-watt monophonic FM transmitter at the studio. To avoid interfering with other stations, an ordinary AM station was required to limit its bandwidth to 15 kHz in those days (and only 10.2 kHz now). I suspect that Gary didn’t worry about that. He fed full-bandwidth audio into his system, and it sounded great.

But back in 1949, before any signals were in the air, Bob and Jim agreed it was important to sell the idea of a radio station to the college president, William Stevenson. They took the president to dinner.

They noted that the structure at 32 East College Street was available and “maybe we could move the Review, the HI-O-HI, the planned radio station and the literary magazine Yeoman into the building. Stevenson was absolutely enthralled with the idea of the radio station and of moving into a communications building. He was so pleased that he even gave us cigars.” {5}

In Loco Parentis

However, said Roger, the president “identified the major problem, which was not something we had anticipated — the Dean of Women’s possible objection to having a den of iniquity, in which who-knew-what could happen to female students.”

At the time, Oberlin was much concerned with its responsibility “in the place of a parent” to protect the virtue of the precious children who had been entrusted by their parents to the College. Especially the girls.

Bill remembered that a decade later, “we decided that we would do a remote broadcast of a women’s basketball game. We had a hell of a time with the women’s Athletic Department. Not getting in, because spectators could go in, but they wouldn’t let us do it live. We had to tape the game and let the department review the tapes. I don’t know what they were worried about, but it was a really big deal.” {27}

Fred Cohen ’57 pointed out, “Current students don’t realize what went on in our day with the women’s dormitories — no men allowed above the first floor. The only time we really were able to get upstairs in the women’s dorms was through radio-station business. It seems that all of our box wires came in on the second or third floors. I remember going through Talcott, and they’re yelling, ‘Man up, man up.’ Going up to check the wires, of course.

“There was also a problem with freshman women using the telephone after 10 o’clock,” Bill added. “We had a request show — ‘5-1201’ — on Saturday nights. The Dascomb house mother was particularly strict, and they couldn’t use the normal telephone system. They’d have to sneak down to the pay phone in the lobby and hope the house mother didn’t catch them. So one Saturday night we broadcast Morse code.” Women at their windows in Dascomb could use lights to blink out their requests to the DJ’s at the station. {27}

Back in 1949, Roger remembered, “Reynolds and I put our heads together and we decided to strike preemptively by coming up with a code of conduct that we would go lay on the Den of Women. We thought that if it were suitably rigorous, it might head off any discussion of perils. So we rode our motor scooters out to the President’s house and presented him with the first draft of a code. We said the center would be run by responsible people behaving in responsible ways with both feet on the floor at all times, always three or more persons present. By golly, it worked. We had hanging on the wall four or five rules about how many people had to be in the place, what hours and so on.” {5}

East College Street

“Roger Brucker was the founding father of KOCN,” Bob remarked. “He gauged campus opinion. He talked to students, taking polls. He built the support of campus organizations so that they could see an outlet for themselves in a radio station. And then he built a business case that today would do any businessman proud, and sold it to the trustees, the president and the students.” {6}

Roger remembered, “We had an unusually smooth time of moving into that building with a lot of enthusiasm. Momentum was gathering among people who looked at the station as an interesting technical challenge, others who saw it as a programming outlet, others who saw it as a chance to do what they’d always wanted to do as kids.” {5}

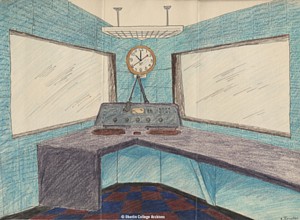

|

He got out his crayons and drew perspective presentation sketches of how the radio station might look: Studio A (on the right) and control room (below). The Oberlin Review editorialized on May 3, 1949, “The proposed station is currently still in the dream stage, but it is a highly attractive dream. We hope that it soon develops into the reality of a campus station, student operated and student supported, and free from the annoyance of constant commercials.” |

|

|

|

Bob said, “We received funding of $600 through Roger’s efforts to acquire equipment (including two turntables for $30 and 15,000 feet of coaxial cable for $225), build studios, and — most difficult of all — to get our signal transmitted from the studios at 32 East College Street to the far-flung dormitories all over the Oberlin campus. That proved to be nearly our undoing. First of all we had to design and build all of the equipment by hand, because the cheapest way to do it was with parts.” {7} |

Roger explained, “We understood the political process well enough that we wanted to have very high visibility as early as we could, given the constraints of money. People asked how we could do anything with the initial $600. During that summer, we ended up with three or four rooms dedicated to the radio station. So the minute students began to arrive, we scrounged — two-by-fours, paint, nails, carpeting for soundproofing, Kimsel insulation, plate glass — all sorts of things from all sorts of people who were expert scroungers. Walls went up to create the transmitter area, the booth, Studio A and Studio B. There was a virtual army of people working. The idea of getting all of this edifice up so people could look at tangible things was a critical part of getting the mass up to the point that it would go forward.” {10}

“Here are the things the radio station did for those of us who were involved in the formative years: It put us in contact with real problems where we as students had to go out and negotiate with real people. There were 99 reasons why you couldn’t do something, but we recognized that there were probably a few ways that you could do something. We fell on powers of persuasion, logic, chicanery and the idea of networking, which of course is very popular now. We didn’t invent it, but we certainly discovered that if you knew somebody who knew somebody who could get an introduction, that would go a long way.” {13}

Bill Hayward ’51 recalled the first week of test broadcasting in May 1950. “We had to have something musical that students could listen to, especially during the dinner hour, so we borrowed records from my roommate, Rex Tucker ’51. We bought a new Baldwin baby grand piano for $500. Most programming was music and many students played the piano, which was a very important source of quality programming. We acquired a broadcast-quality microphone. It was an Electro-Voice 630 microphone and it probably cost us around $75 to $100, at the time a major, major expenditure.” {9}

|

|

Seventeen years later, in Studio A after the station had moved twice, I sat at what I assume was that very same piano. (In the foreground is Marc Krass.) By then our studio microphones were mostly the EV 664. |

Bob continued, “Finally in the fall of 1950 — I believe it was Sunday afternoon, November 5 — we went on the air permanently. We had a gala open house for students, and President Stevenson did the first broadcast. We were off and running.”